Identifying the ‘Fruit and Root’ of Systemic Racial Inequity

February 9, 2022

At a Glance

Creating an equitable learning and work system means looking at the root causes of racial inequity, not just the impact.

Paul Batalden, a professor emeritus of community and family medicine at Dartmouth’s Geisel School of Medicine, was known for his saying, “Every system is perfectly designed to get the results it gets.” While Batalden was referring to inefficiencies and high costs in the health care system, his idea applies to our education system as well. A look at the stark racial disparities in educational outcomes reveals that the education system fails to be a great equalizer. Calls to reform a broken system ignore a harsh truth: our nation’s education system isn’t flawed or broken; it was intentionally designed to produce the disparate outcomes that disadvantage Black and Latinx youth. Over time certain systemic practices have changed—separate and unequal schools, or disciplinary practices creating pipelines to prison rather than postsecondary education—but the education system and many other systems formed at the time this country was founded and slavery was legal continue to create racial inequity in America.

Jobs for the Future (JFF) has launched a community of practice called Building Equitable Pathways that’s attempting to unearth the fundamental causes of inequity in our current systems, and create a more equitable education and workforce system, beyond the school reform movements of the last several decades. We believe that systems that may seem impermeable can be changed. We also acknowledge all the hard work that has already taken place to disrupt relics of oppression that are promoted in the current systems. Together, we seek to increase our collective capacity to hold ourselves accountable for not succumbing to the tired methods of data, policy, and equity practices that do not get to the root causes and for disrupting historical and ongoing inequities in the design and outcomes of our education and workforce systems.

This work has led us to the conclusion that while systemic inequity may be intentional, it is not inevitable. It can be changed if we are willing to challenge existing framing and assumptions about the problems and how to solve them. A framing that suggests the system is designed to be inequitable can be more daunting than framing the system as broken, but this framing is a key part of reforms that can address fundamental or functional equity issues.

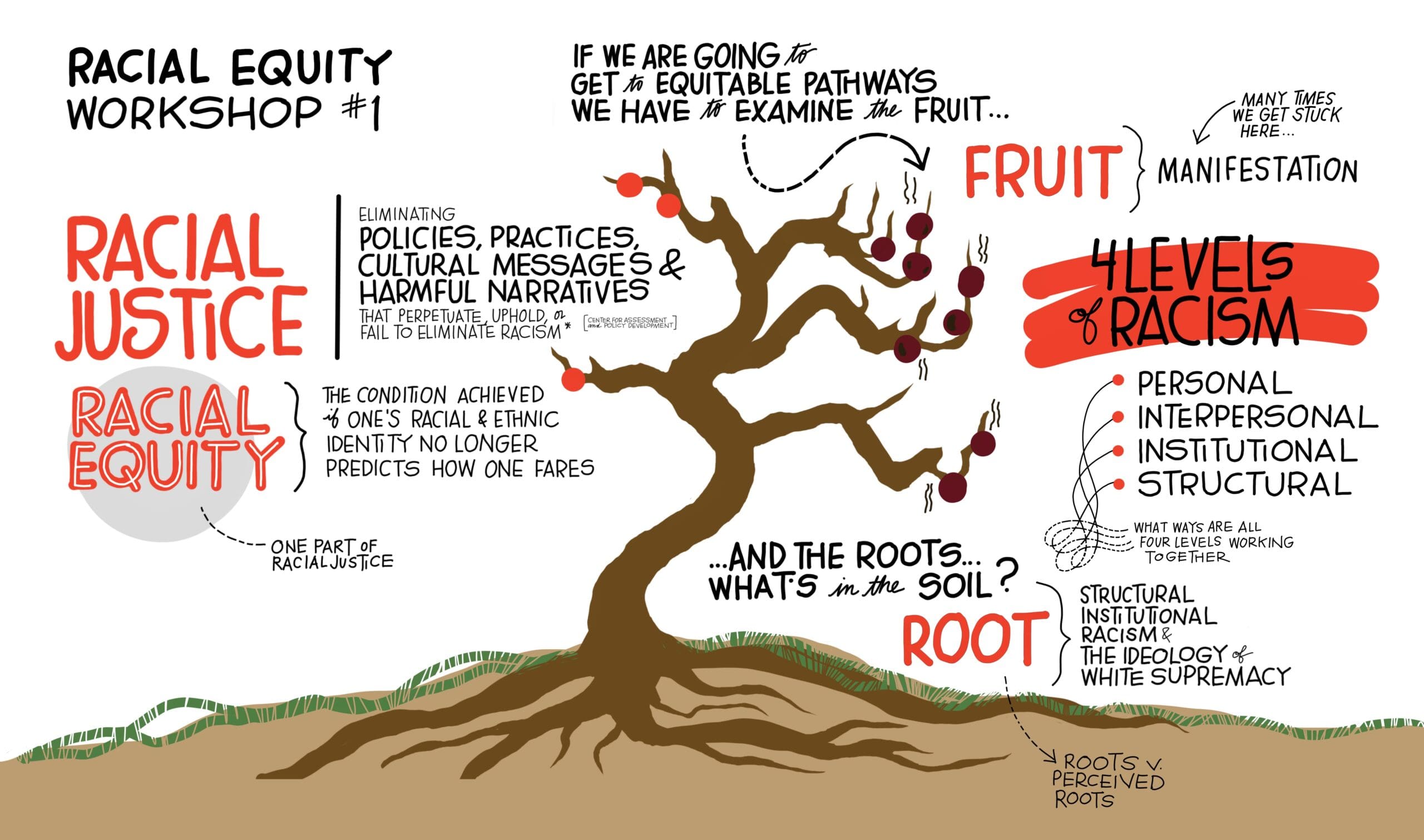

Understanding the ‘Fruit’ and the ‘Root’ of Systemic Racial Inequity

Clair Minson, a leader in the field of racial equity in the workforce, offers a “fruit and root” metaphor to differentiate between the causes and effects of racism. The “fruit,” Minson explains, is the outcomes of the racism embedded within systems, visible and magnified. For example, when Black and Latinx young people are disproportionally directed to pathways that lead to low-wage employment, the intervention is typically focused on strategies for increasing representation in pathways or eliminating pathways to low-wage jobs, often without also examining what factors have created this disproportionate representation. Most often, the “fruit” gets most of the attention because it is most visible and seemingly easier to address.

However, achieving racial equity requires that we acknowledge the “root” as well—the institutional and systemic causes that uphold and perpetuate racial inequality:

- Individual biases against other individuals or groups and internalized biases against one’s self based on a socially disadvantaged racial identity

- Interpersonal dynamics and ways individuals engage other individuals and groups of individuals who have been historically excluded by law or custom from societal benefits and resources

- Institutional policies, practices, and culture that keep people marginalized based on race or ethnicity, or perpetuate segregation and social sorting, and that elevates one race and diminishes others

- Structural features of society, including systems, policies, cultural norms, and representation, that collectively operate to maintain racism and the ideology of white supremacy.

Collectively, these factors work together to maintain inequity and perpetuate white supremacy—the normalized assumption that white people are superior to others—within systems and programs. In Martin Luther King Jr.’s 1960s Birmingham, the law codified these assumptions of white supremacy and explicitly required interactions that sustained a racial caste system. In our time, narratives and practices that promote white supremacy are perpetuated through custom and practice, both largely invisible but still contributing to the manifestations of racial inequity and racial injustice.

Our tendency to address the fruit is important because students are experiencing it, so we have to call it out as well.

But it is equally important (dare we say critically important?) to get to the root causes. What are the biases that education leaders and decision makers hold about Black and Latinx youth? How are negative biases reified through data? How are biased assumptions institutionalized through institutional and systemic policies, culture, and norms? Learning to identify and address the root causes of inequity is an area of growth for the work of building equitable pathways.

How We Address the Root

The practice of naming the manifestations of racism and exploring the root causes will change how we name and frame challenges that we face on the journey to building equitable pathways. It will also potentially disrupt our existing assumptions and practices and how we make decisions.

Intermediaries in this community of practice are supporting the design, scale, and delivery of education-to-career pathway systems designed to prepare young people for seamless transitions to postsecondary education and training and careers. The core hypothesis and driver for this work is aligning education and training from the pathways to labor market demands and meeting employer needs. This is a commonly accepted principle and best practice of pathway designs.

However, “meeting employer needs” without examining the root causes of inequity in the labor market can create problems for Black and Latinx youth transitioning into the workforce. Robin Walker, the executive director of the Philadelphia Robotics Coalition, recently provoked members of the community of practice when she shared a past work experience from an organization’s pathway training program: a few weeks into the on-the-job training portion of the program, the employer partner raised concerns about the young people from the organization—all of whom were Black—and wanted to create a separate and supplemental training program for the Black youth. The primary concerns were not about performance and skills but about “fit” and “professionalism.”

While systemic inequality may be intentional, it is not inevitable. It can be changed if we are willing to challenge existing framing and assumptions about the problems and how to solve them.

Concerns around fit and professionalism when it comes to Black people in the workforce have been closely tied to discriminatory practices. In the context of the fruit and root analysis, the situation the students encountered may appear to be the “fruit” of an inequity issue in this workplace—a visible outcome of internalized bias and prejudice. However, it is in fact the “root:” a deep-seated belief in the concept of “fit” itself, manifesting at the interpersonal and institutional levels. The seemingly neutral concern about “fit” has proven to be problematic, and is used to cover for a preference for a homogenous culture in the workplace. It surfaces the tension between diversity (representation) and inclusion (sharing power). Beliefs about “fit” have often been correlated with excluding Black and Latinx candidates from predominately white corporate spaces: employers want to hire people of color, but the people of color they hire are subtly forced to conform to existing norms—of dress, behavior, speech—to truly belong. Without any clarity on what “fit” means or how to demonstrate it, this hiring criterion tends to focus on individual attributes while ignoring how biases about race and gender impact hiring.

After talking with the employer and students, Walker raised the concern that the challenge was not that the young people were not ready for the employer, but that the employer was not ready to fully support a racially diverse workforce. Working closely with leadership in the organization, she ultimately advised ending the relationship with the employer rather than making the young people of color participate in a separate program. Leadership, after many discussions, agreed with this recommendation.

While this decision did not bring about a transformation on the employer’s part, it called attention to the harmful narratives in play, held the organization accountable for its issues, and ultimately put the well-being and experience of the Black and Latinx youth at the center of the decision, disrupting the dominant practice of prioritizing employer needs over students’ experiences. While it is important for students to be ready for the workplace, this organization also held to the principle that employers can’t claim to prioritize diversity initiatives if they are not prepared to create a workplace culture that is ready to include, without requiring assimilation, Black and Latinx students. Transformative employers take the next step to create diverse, equitable, and inclusive workplaces where Black and Latinx youth thrive.

I was prepared for the job, but not for the racism.

Such disruptions take individual and institutional courage. As a Black woman in a predominately white organization challenging a predominately white employer’s DEI practices, Walker knew that she was advocating for Black youth from a particularly vulnerable position. The landscape of the field makes this a common vulnerability as the majority of organizations serving Black and Latinx youth are predominately white and led by white leaders. Walker admitted that she recognized the risks of speaking up, but said she couldn’t advocate for equity and social justice while staying silent about the racism in the settings where she placed her students, no matter the cost.

Our Work Ahead

The work ahead is to name and uproot the ongoing norms and practices that continue to disadvantage Black and Latinx youth in our education and workforce systems. While daunting, it gives us the opportunity to act in the current window of racial reckoning to center and prioritize Black and Latinx students and build pathways that are equitable in design and yield equitable outcomes. Minson has demonstrated the need for a deeper analysis and gained tools to name the manifestations of racism and analyze the individual, interpersonal, institutional, and structural practices that perpetuate the inequities in the pathway programs. Walker showed how to disrupt the assumptions at the root of inequitable practices and require collective accountability for anti-racist practices. Her student reminded us that racism exists and students will experience racism whether adults admit it or not. As one student told her, “I was prepared for the job but not for the racism.” We need to listen to students and develop race-specific strategies to address the race-specific problems they encounter in the workplace.

It takes courage to truly prioritize equity as the north star, yet there is no alternative. Archbishop Desmond Tutu is no longer with us, but his teaching holds true: “If you are neutral in situations of injustice, you have chosen the side of the oppressor. If an elephant has its foot on the tail of a mouse and you say that you are neutral, the mouse will not appreciate your neutrality.”

With truly equity-focused pathways in our education and workforce systems, we can disrupt a harmful status quo that has been entrenched for centuries. It is daunting work to unlearn habits and build new practices but it’s not impossible. We know it will take time, but the time to act is now.